Introduction

Many papers, articles and conference presentations [1] have been devoted to the discussion of the problems and the scholarly challenges presented by the design and the development of digital editions. However, not as many contributions are to be found about other essential aspects of managing such projects, aspects that are also a direct consequence of the introduction of scholarly editing into a digital environment – for instance, consequences of collaborative work in the Internet age, migration to new technologies during a project’s life time, and the relationship with publishers in the case of a hybrid publication.

By their nature, digital humanities research projects are mostly collaborative, as the necessary skills to undertake such projects are very rarely to be found in a single person. This is perhaps the biggest change that the use of the computer has introduced into scholarly editorial work which for centuries was often the effort of a single scholar. Furthermore, the present availability of the Internet and of web-based communication tools have enabled distance teamwork at a level unimaginable only a couple of decades ago. These factors create issues which were previously almost unknown in the humanities such as a project workflow, project data and communication management. [2] The task of coordinating the work of several people, all of them managing in various ways the same batch of data, possibly working from scattered locations, with different working habits and different skills, is by no means to be underestimated and, if not done properly, can jeopardise the project as a whole.

Digital objects suffer from rapid obsolescence and therefore, especially in long-term projects, it is often necessary to upgrade the whole data-set to the latest version of a specific encoding language or piece of software, lengthening the timeline and increasing production costs.

The possibility provided by encoding languages to easily produce both a digital and a print edition from the same source material makes the creation of so called hybrid publications broadly achievable. Nevertheless, such an opportunity opens the way to a new set of problems, from data management to relationship with publishing houses.

This article will discuss the aforementioned issues, using the correspondence of Giacomo Puccini as a case study for the preparation of such a hybrid edition. This is the work of a research project in progress at the Centro Studi Giacomo Pucciniin Lucca, coordinated by Gabriella Ravenni (scholarly edition) and by Elena Pierazzo (digital framework). [3] The Progetto Epistolario (PE) [4] is a demanding project due to the large quantity of the preserved material. At present, about 6.500 letters have been traced, but this number noticeably increases each year (about 400 units per year) thanks to a deep search of libraries, private and public archives, collections and antiquaries’ catalogues. The existence of at least 10.000 preserved letters can be easily foreseen.

The Centro Studi has designed this publication to be its main project for the next ten years; the first volume of the correspondence – all the letters written before 1897 – is supposed to be finished in 2008, in time for the end of the Puccini Celebrations. These celebrations have begun in 2004 for the centenary of Madama Butterfly and will end in 2008 with the 150th anniversary of the composer’s birth.

Hybrid edition: why and how

The publication will be in both print and digital formats. This choice is in response to the different needs of the academic and the larger audience. A print publication, in fact, is more established in the academic world as it gives a sure physical consistency to the work, meaning that it produces a physical tangible object that can be easily quoted, while digital publications are more likely to change their Internet address and their content can be silently modified. Furthermore sceptics of digital media can use print publications without discomfort.

Scepticism, uneasiness and lack of confidence in the academic world (especially in the humanities) toward digital resources have several motivations. Probably the most important of these is the supposedly ephemeral nature of digital products and the difficulty in judging their objective scholarly value. While humanities scholars are able to quickly evaluate the quality of a print edition (the reputation of the publishing house, the accuracy of the layout, the quality of paper, the reputation of the editor, et cetera), »texts on screen look remarkably alike, despite profound differences in quality«. [5] And even with more thorough inspection, unless scholars are able to decipher acronyms like XML, TEI, CSS, W3C, RDF, XHTML et cetera, [6] and understand whether it is good or bad to find them in a website, the quality of a digital edition remains undisclosed.

On the other hand a digital publication can be used for searching, linguistic inspections can be variously indexed, and data can be presented according to different needs; furthermore the publication can be easily updated even after its first issue – a point of capital importance for the PE, considering the constant increase in the number of known letters – and can be accessed from all over the world for just the cost of the internet connection. [7]

Both publication methods have their strengths and weaknesses, so we thought that in order to take advantage of the former and minimize the latter, a hybrid publication would be the best solution: »[…] experience has convinced the majority of specialists [id est scholars of a specific discipline] that ›e-only‹ will not be the solution. Rather, a hybrid system is required which offers the same contents in both formats, adapted for different media«. [8] Moreover, digital and print editions answer different needs in their users: while a print edition is essentially made for reading, a digital edition is meant to be used for searching and browsing, and to provide different perspectives on the data.

Despite the advantages of having both a digital and a print edition, the twofold medium involves many difficulties in the production phase. A print edition and a digital edition, for instance, organise information and editorial interventions differently; for example, a footnote giving evidence for the name of a person in a print edition can be substituted by a hyperlink to an ancillary Index of Names document in a digital edition. The same applies for internal cross references: a footnote in print can correspond to a link in a digital product; therefore the format chosen for the textual digitisation needs to be flexible enough to enable different organisation of the information according to the media.

For sustainability reasons we had discarded from the very beginning the possibility of creating and maintaining two versions of the texts: any improvement or correction would have to be done in two different places, increasing the workload and the overall project costs and, soon or later, lead the texts to be unsynchronized and therefore unreliable. [9]

The easiest way to manage the dual output is to produce it from the same master document, the more suitable format being an XML-encoded text that allows the encoded features to be handled differently by means of different stylesheets (XSL and FO stylesheets), producing printable or browsable versions, each of them managing such features in the way most suitable to their media type.

Subject of the edition

The design of the encoding model for PE needed to consider firstly the content of the edition. Different types of Puccini’s documents were taken into consideration – conventional letters, telegrams, postcards, illustrated postcards and cards – and we discussed whether to include documents like petitions and applications (for scholarships, for instance) in which we found Puccini’s autograph signature, and also dedicated photographs and scores.

The selection criteria for the documents was »letter like«, however the debate among scholars on What is a letter? suggested that there is not a unequivocal answer. [10] With no pretensions of giving a theoretical response but instead being purely pragmatic, we have considered a letter to be a written document that:

• is an asynchronous form of communication;

• is written by a sender (singular or collective);

• is addressed to a receiver (singular or collective);

• conveys some sort of information from the sender to the receiver.

Given such restrictions, we considered that, even though dedications might help to reconstruct some moments of Puccini’s biography and give important evidence of the relationships between the composer and a particular person or cultural sphere, they cannot be considered correspondence without forcing our definition as they have little or no informative content. Petitions and applications have given us more problems, as they theoretically could fit the definition, but, with the risk of being criticised, we considered that they are more a sort of public act, the desired outcome of which is normally itself a public act such as a law or a decree. Nevertheless, in consideration of their historical and cultural relevance, we decided to include such material as well (both dedications and petitions), even if with a different status, that is by creating an appendix of so-called Documents to complete the edition.

The encoding schema

The choice of the encoding schema has been a very important step as well. The idea of creating a new encoding schema has been soon discarded, as that would have prevented us from sharing our work with the international community.

Looking at existing schemas, we first considered adopting TEI P4, [11] TEI being the de facto international standard for text encoding and offering both a wide range of elements to support scholarly editorial work and also a large community of users within which to find the support that any research project needs. Nonetheless, after starting to encode a batch of letters, we soon realized that such a schema was unable to accommodate some peculiar characteristics of correspondence such as postmarks, headed paper, or envelopes. The same remarks can be extended to the new TEI release, the P5 schema: [12] without a radical customization they are not suitable for encoding correspondence.

We then discovered that someone else had already done such a customization of the TEI model, creating the DALF DTD, that is an encoding schema based on the TEI P4 DTD and realized by the Centre for Scholarly Editing and Document Studies (CTB), a research centre of the Royal Academy of Dutch Language and Literature in Belgium. [13] Such a DTD, in fact, includes all the features we pointed out as distinctive of correspondence. We therefore converted all the encoded letters into DALF and we expect to convert them again as soon as, and if, the DALF DTD will be converted into TEI P5 or when the latter will incorporate new elements for the encoding of letters. Several months have been spent in elaborating the new encoding model and converting into DALF both the XML files and the different stylesheets used in the project. The advantages were considerable, though (for instance, we were able to encode without ambiguity or tag abuse typical letters parts such as envelops, sender and addressee), making the full process worthwhile, even if long and costly.

For the encoding of ancillary documents (such as petitions and dedications) we adopted the TEI P5 schema that significantly improves the manuscript description section with respect to the P4 version. As the Master Project DTD [14] inspired both the letter description section included in the DALF DTD and also the P5 manuscript description section, it has been easy enough to manage, index and query both letters and documents with the same tools, though only by creating a second set of stylesheets and other scripts. If the corpus of letters will be converted into P5, we might be able to simplify the processing architecture by maintaining a single set of scripts.

Names management

The management of proper names has involved the creation of authority files. We found dozens of thousands of names in our corpus of more than six thousand letters: personal names, place names, names of institutions, and titles of operas and other works; all of them needed to be regularized and managed in order to produce indices both for the digital and the printed edition and also to enable any meaningful searching.

Although an RDF-OWL ontology has proven to be very efficient in dealing with similar matters, [15] the lack of simple editorial tools and the impossibility of having a full time software developer [16] prevented the adoption of such a technology. So we opted for a MySQL database instead, provided with an ad hoc intuitive web interface, able to manage personal names and nicknames, place names, embedded institution names (theatres, academies of music, et cetera), operas’ titles and operas’ characters. The database is also able to produce indices for all the aforementioned entities in the form of XML TEI files. Those indices are then transformed into HTML to be embedded within the website (via XSLT) and into a printable format to be used by the print edition.

Beside those data types of names, a database of paper headers sharing the same infrastructure has also been created. In this case the database is meant to be only an internal editorial tool as it has proved to be of a capital importance for dating and locating letters, but we expect it will have little relevance for users. Therefore, we do not expect to produce any kind of index for paper headers as for other types of data such as names and opera titles.

Work teams and management challenges

The Project team is divided into three sub-teams:

1. an editorial team, composed of musicologists, historians of music and of opera;

2. a technical team which includes encoders, an analyst, a web master and a web programmer;

3. an editorial staff in charge of coordinating the communication between different members and managing the workflow.

Members of the editorial team have different skills (both from a cultural and a computing point of view) and background, and are scattered all over the world in different locations in Italy, Germany, Switzerland and the United States; all of them work on a voluntary basis (we could not afford the project, otherwise). The editorial process requires that each single letter is seen and annotated by all the members in turn, as each of them will add different kinds of annotations (musicological, historical and linguistic).

These particular characteristics of the editorial team (different skills, different locations and voluntary work) have important consequences for the workflow and for the technical choices of the whole project. Before starting work on the project, none of the members of the editorial team or of the editorial staff was aware of XML and XML-related technologies. Despite an XML focussed training, because of the difficulties (due mostly to distances) of providing proper long-term assistance after the training, combined with some degree of digital scepticism, they resisted converting their working habits from their favourite word processor to XML. As a result, part of the work is conducted in a WYSIWYG environment (which is unsuitable for data processing) and part in XML, with all the resulting complications in project management, quality assurance and, consequently, workflow.

The technical team is equally disparate, spread between Italy and the United Kingdom, and furthermore it lacks key figures such as a systems analyst or a programmer: again, this is because of funding issues. To face the technical needs of the project, the choice in this case was to commission standalone products from commercial private companies which develop their software in Open Source frameworks; this solution kept our budget under control on the one hand, but in the meantime it has posed several issues in integration as those products were never designed to be combined within a single framework.

A major issue for such a scattered and differentiated project team has been the management of communication and the exchange and maintenance of data. In the beginning email was used for all the above-mentioned tasks. Indeed, email remains undoubtedly the primary means of communication among people, but very soon we understood that it was not meeting all our communication needs and was not suitable for data exchange, backup and management. Therefore our communication system was upgraded to include chat and web-based voice systems such as Skype [17] for regular and occasional discussions. On the other side, storage, management and backups are now guaranteed thanks to a web and server based versioning system named OWL. [18] This tool proved to be much simpler to use than other popular client-server solutions like Subversion [19] as it displays the file structure in a similar way to the users’ normal operating system; on the other hand this system provides only basic versioning functionality. The particular configuration of our project team, in fact, suggested that simplicity of usage and user-friendly interfaces should be top priority in any development and management choice, even at the expense of efficiency. As all of the people in the editorial team work on a voluntary basis, it has been decided that allowing them to work in an environment in which they can feel confident was the only way to maintain a high commitment to the project. The transcribed letters are therefore stored and managed within that environment, being moved around different folders during their life cycle according to their editorial status.

The website and the quality control architecture

The project website [2] has been conceived both as a publication tool and as an internal management device. The letters are managed and queried by a XML database (eXist) [20] while the publishing infrastructure is based on PHP. [21] At present the database that manages the different types of names and the website are totally unrelated, meaning that the indices produced by the database need to be manually transformed into HTML/PHP and then loaded into the website.

On the server side, we were lucky to obtain the support of the Municipality of Lucca that kindly offered to host all our web products for free – and for an indefinite time – and provided us with systems support, even if sometimes we experience delays and difficulties in changing the settings of the server (as the server is not under our control); this makes integrating the tools (namely the website infrastructure and the database) indeed highly desirable but at the same time difficult to implement.

In all digital edition projects, especially those involving large teams, quality assurance is perhaps the most important issue, so a good checking infrastructure is a key feature for the overall success of the project. In a project that is expected to run for ten years, it is vital to keep control of editorial choices and consistency in markup. The checking facilities which were implemented are of a composite nature and make use of several technologies. In order to be really effective, they need to test the materials in different ways and from different points of view. For instance, while in a print environment it is normally enough when the document looks correct, in a digital framework data also need to be encoded correctly not only from a syntactical but also from a semantic point of view, as the querying and the indices will easily highlight any inconsistencies to the point that they might fail to produce the expected results.

At present the following facilities are used at various stages in the workflow:

• XSLT based: a set of checking pages present the transcribed letters in different ways, used by the encoders and by the editorial team for editorial purposes; they are also the instruments used to report any correction to be done to the XML files. The checking pages stage the texts in two ways:

- presentational layout: features such as editorial corrections or footnotes are highlighted and therefore can be easily recognised in the reviewing or proof-reading process;

- tabular layout: the structural markup is highlighted.

• xQuery based: a querying system based on eXist that mirrors the public website is used to query dates, names and free text in order to check the consistency of the most critical fields. This instance is used mostly by the editorial team to spot errors and by the editorial staff to monitor the project’s progress.

• Database based: XML files are regularly uploaded within the aforementioned database to check consistencies in references of names, matching the ID within the database and the one attributed to the names in the files. This facility is mainly used by the encoders in order to verify the accuracy of their work.

Workflow

Let us now consider the life cycle of a transcribed letter (hereafter referred to simply as a »letter«) in terms of workflow:

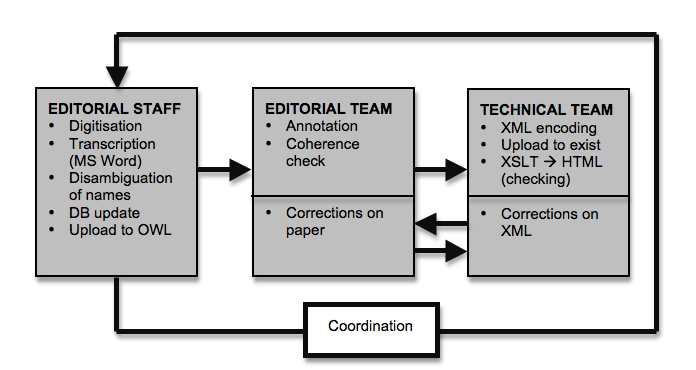

Figure : A letter editorial life cycle

The three sub-teams manage the letter in turn in a recursive way, as follows:

a) Editorial staff:

1. the letter is digitised from a repository (archive, library);

2. then it is transcribed into a MS Word file;

3. references to names are provided by a database identifier;

4. in the case that a name cannot be traced within the database, the missing entry is created;

5. then the letter is uploaded into the versioning system.

b) Editorial Team:

1. the letter is annotated by the members of the editorial team in succession who add biographic, background, musical, and linguistic notes;

2. then the letter is fully revised by the project director in order to regularise the annotations and to point out any inconsistencies;

3. if it is approved by the project director, the letter is passed to the technical team, otherwise it remains in the editorial team until a provisional agreement is found. The most common disagreements concern dating and identification of people

c) Technical Team:

1. the letter is manually encoded in XML;

2. then it is uploaded into the private eXist instance;

3. and it is finally converted in a set of HTML checking-pages.

d) Editorial Team:

1. the HTML versions of the letter are checked;

2. the letter is queried together with the others in the private eXist instance;

3. errors are reported to the encoders via email or in paper, using print-outs of the checking pages.

e) Technical Team:

1. the letter is corrected according to the requests of the editorial team;

2. then it is again uploaded into the private eXist instance;

3. and it is converted into HTML checking-pages.

f) Editorial Team:

1. the letter is approved and published.

The uploading of the letter into specific folders within OWL marks passage from one stage to the next; stages D and E may repeat several times. The overall control and coordination of the work over the different stages is managed by the editorial staff with the help of a set of spreadsheets and the private eXist instance.

Publishing a hybrid edition

A sample of 150 encoded letters (the so-called Lettere Lucchesi, being all letters that are preserved in libraries and archives of Lucca) is available for reading and querying from the project website, but we do not expect to increase this number in the near future. In fact, the project faces further complications due to a complex relationship with the publishers of the printed edition. These publishers are sceptical of the prospect of having the texts freely available on the Internet as they fear that this will compromise the commercial success of the published product. This fear is probably due on one hand to the novelty of the form (at present, no other hybrid scholarly edition – web and printing – has been ever published in Italy, and very little has been published abroad), [22] and on the other hand to the still uncertain theoretical and practical understanding of the relative strengths and weaknesses of the two formats and of the advantages of having the two side by side. Very little has been written about dual (or hybrid) publications (the only exceptions seem to be Ciula/Lopez, and, from a different perspective, Lucius [23]) or about the ways users utilise the two formats in relation to each other. We designed our project on the assumption that each format would enhance the other, where:

[…] the reading of the edition and the seeking of the information related to it (persons, places, subjects and any other interesting clue to its historical study in a broader sense) is a global process that does not stop when the book is closed or the browser shut. We believe that, when supported by a deep interest in the material, the connection between the two publications is created in a rather fluid manner. [24]

Many web usability studies [25] show how tiring and frustrating it is to read long chunks of texts on the screen and that when a long text is to be read on the screen, web users normally print and read it on paper »since the display of documents on screen has not yet reached its maturity«. [26] On the other hand many articles inform us that a digital publication is more likely to have a higher impact on the academic community than a print one. [27]

Recent studies have discussed the so-called Open Access »green road«, meaning that »titles initially published in classic paid-for media would be made available free-of-charge on the web […] after a certain period (6 months is an often-mentioned time scale for such schemes)«; [28] this is supposed to guarantee open access to the resource without damaging the publisher’s revenue; again the words of Lucius are particularly to the point (and are particularly interesting given that the author is a publisher himself):

Offering the document on the author’s own website gives rise to only minor concern and should cause hardly any significant loss in the publisher’s revenues. A general university repository, too, could be acceptable from the publishers’ perspective. [29]

Furthermore, studies demonstrates that, after the first 6-12 months from first publication, the use of the web resources increases, and therefore

[…] it might be attractive for publishers to make available electronic copies from print journals to a wide audience at least after a short embargo time to improve the publicity and acceptance of the own products, a strategy the ››Social Science Open Access Repository‹‹ (SSOAR) invites interested publishers and journals to. [30]

For these reasons we hope to find a compromise with the publisher in the months to come.

Conclusions

The case study presented here has offered the opportunity to discuss matters of increasing importance in the digital humanities community. Moving the editorial work into a digital environment implies many different changes in the way scholars work, both in terms of work habits and their relation to their own product. Shifting the editorial work to a collaborative framework implies that decisions, crucial choices and practices have to be discussed, agreed upon and shared; in a digital environment, this normally also implies the development of tools and management techniques, especially when the team in question is geographically scattered.

If the outcome of the research and editorial work is also in a digital format, then the different medium also requires radical changes in the methods of conducting the research itself, and even the long-established relationship between authors and publishers needs serious reconsideration.

Digital editions are not completely new objects, [31] but they are still fighting for full academic acceptance both at the institutional and the personal level: institutional issues include research assessment exercises, funding bodies and the way in which academia evaluates digital output when determining career progression, while personal issues include the difficulty of a scholar to change working habits and learn new techniques, and the evaluation of a digital resource. According to Peter Robinson, such an academic scepticism result mostly from the lack of usable tools, [32] and certainly the PE case study demonstrates the prime necessity for user-friendly and usable tools. Nevertheless, the implementation of out-of-the-box tools that Robinson has in mind is, in my opinion, a very difficult task to add to the digital humanities agenda. This is because humanities data have a very high rate of variation (in terms of disciplines, object of studies, approaches, et cetera), and even when similarities do exist, the differences are important enough to imply that designing tools able to cope with such variety would be a very demanding task. Furthermore the current standards that are used at present (and, with good probability, also in the future) for the creation of scholarly digital editions – for instance TEI, to start with, but also ontologies, metadata schemas, et cetera – are all highly customisable and flexible, which is one of the main reasons for their success. Again: on the publication side, different models for scholarly editions have been developed by different disciplines in the humanities (and even in different countries within the same discipline), so that there are now many such models and it is hard to imagine a single tool which can produce the many very different outputs which these models require. Robinson thinks of the user as the solitary scholar that on her or his own is asked to deal with all the aspects of producing a digital edition. However, most digital editions are more likely to be the product of a team, in which the required technical expertises are normally to be found, with the result that editorial tools such as the one pictured by Robinson are certainly highly desirable but less likely to be crucial. With that I do not imply that tools cannot be designed, but that most of them (and particularly the editorial ones) need to be tailored to specific projects and needs; in this case I agree that issues such as user-friendliness and simplicity need to be considered as primary concerns.

On the other hand, in my opinion, these difficulties in use do not explain all the resistance a digital product encounters. I suggest that the answer is to be found in the difficulty of evaluating the quality of digital products in the academic world and in doubts about the long-term persistence of such products on the web. In addition I would say that a survey on the reception of digital and hybrid editions is still a desideratum, combined with a revision of the role of publishing houses in the editorial process.

The digital humanities community, represented by research centres, associations and single scholars, will have to face such challenges in the near future in order to achieve a full digital revolution in the humanities.