The title of this article has two antecedents. The first would be familiar to those in the TEI Community. It is a reference to Elli Mylonas and Allen Renear’s introduction to the selection of papers commemorating the 10th Anniversary conference of the Text Encoding Initiative (TEI) held at Brown University in November 1997. The introduction to the volume was entitled »The Text Encoding Initiative at 10: Not Just an Interchange Format Anymore – But a New Research Community.« The articles collected in that volume spoke to new theoretical perspectives in electronic text creation, covering topics as varied as the TEI within the newly-released XML standard, the TEI Header, Writing System Declarations, and a topic is as topical today as it was 10 years ago, the encoding of textual variation. [1]

The second antecedent would resonate with the Irish in the audience or those familiar with Irish cultural studies. It is Thomas Davis’s rousing rebel song A Nation Once Again. The song embodied the hopes and dreams of generations of Irish who prayed, fought, and lobbied for freedom from England’s rule. The song still resonates with Irish around the world as in a 2002 BBC World Service global poll of listeners A Nation Once Again was voted the world’s most popular song [1].

Both of these antecedents are of particular importance to the newly-established national digital humanities initiative based at the Royal Irish Academy, the Digital Humanities Observatory (DHO). They represent, in equal measure, the technical and cultural underpinnings of a national centre that, on the one hand, promotes international best practice in digital text creation, while on the other, allows researchers the freedom to pursue their intellectual goals in the creation of new modes of scholarly communication.

The DHO is part of a larger national consortium entitled Humanities Serving Irish Society (HSIS) funded under cycle four of the Programme of Research in Third Level Institutions (PRTLI). HSIS was established to develop an inter-institutional research infrastructure for the humanities, and its members are represented by all major research institutions on the island of Ireland: Dublin City University, National University of Ireland Galway, National University of Ireland, Maynooth, Queen’s University, Belfast, Trinity College Dublin, University of Limerick, University College Cork, University College Dublin, and University of Ulster.

One of the primary goals of the HSIS consortium is to build a platform for the coordination and dissemination of humanities research, teaching, and training at an all-island level. The systems and standards that the DHO adopts are the primary vehicles for fulfilling that goal, and issues surrounding the use of TEI for interchange, remediation, and reuse are central to the research needs of the projects being undertaken as well as their long-term sustainability.

Interchange was a concept associated with the TEI early in its history. TEI P3 was referred to as the »Guidelines for Electronic Text Encoding and Interchange«. Early versions of the Guidelines had a chapter entitled »Formal Grammar for the TEI-Interchange-Format Subset of SGML.« The chapter was dropped in P5 as the concepts had become irrelevant in the migration of the TEI to XML. This chapter covered issues of the physical interchange of SGML documents (such as method of communication) while identifying which characters and character sets could and could not be successfully transmitted. It covered minimization techniques such as short references and omission of generic identifiers in start and end tags that were not allowed in TEI as an interchange format. While the technical obstacles associated with SGML in the physical interchange of texts have been alleviated, several large-scale digital humanities projects currently being undertaken highlight challenges in integrating texts created according to the TEI Guidelines across projects in large measure due to semantic inoperability.

While the celebratory nature of the TEI@10 proceedings reflected the realization that TEI was not simply a format for exchanging documents, but a way of representing, describing, and understanding textual evidence, it was also clear that with this broad adoption across many communities of practice the ability to easily integrate these texts into infrastructures beyond those originally envisioned by project creators was becoming increasingly difficult. The design principles laid down at the closing of the Vassar Conference in 1987 (which ultimately became the basis for the Text Encoding Initiative Guidelines) [2] had not only proved robust in developing the Guidelines, but had proved amenable and adaptable to a wide community of scholars working across disciplines and times periods with diverse research goals.

The principle objectives of that first meeting in 1987 were threefold: 1) to design a system that would encourage the sharing of data between scholars and projects; 2) to encourage the development of common tools; and 3) to create a body of best practice in encoding system design. [2] In the twenty-one intervening years, how successful have we been as a community in fulfilling these objectives? Although there are not many tools designed specifically to work with the TEI, in recent years several have been developed, from Sebastian Rahtz’s achievement in developing Roma [3], to more single-purpose tools, such as my own Versioning Machine [4] and Martin Holmes‹ Image Markup Tool [5].

It is probably in the development of a body of best practice in encoding system design that the TEI has been most successful. The TEI Guidelines have become the de facto standard in encoding humanities texts in both the scholarly and library communities. The fairly simple yet elegant design encompasses two complementary blocks of information: the first for bibliographic purposes (the TEI Header) and the second for the source text (within the <text> element). It has not only served the TEI community well, but has served as a model for Encoded Archival Description. There are many other examples of the flexibility and robustness of the design of the TEI. For example, with the release of P5 the Manuscript Description module was officially incorporated into the TEI Guidelines [6]. In this case a specific set of tags provides detailed descriptive information about handwritten primary sources located within a new <msDesc> element. This tagset can be used as the basis for retrospective conversation of existing catalogues or in the creation of new detailed descriptions for materials never before catalogued. It can be located within the TEI header (when the msDesc is describing a digital representation of an original manuscript either as an encoded transcription or as a collection of digital images) or within the <body> when the document being encoded is essentially a collection of manuscript descriptions.

While the TEI community has provided a mechanism to allow communities of scholars to propose new tags or tagsets which would allow them to take advantage of the Guidelines existing strengths while also meeting their specific research objectives, there has been less focus on the first goal outlined above: to provide mechanisms which would encourage ›the sharing of data between scholars and projects‹. Although the possibility of sharing TEI-encoded texts since the advent of XML has become, at least in theory, easier, it is not widespread. Is this because early aspirations for the sharing of TEI encoded documents were unrealistic? Or are the obstacles more profound than the technical? Do they go beyond the semantic to social, economic, and political factors that the designers of the original guidelines could not have anticipated?

The TEI community is at a turning point. The value of the TEI as a standard is increasingly being recognized in the academic community and the cultural heritage sector. Yet, there are still major impediments to the TEI being more widely adopted as a standard, to the texts already in existence being reused in environments beyond which the original creators intended, and in the development of specialized tools for specific purposes. In order to promote the first two points it is more critical than ever that our texts be amenable to semantic interchange: that they are prepared in such as a way that they can be more widely shared between and amongst projects. And despite years of discussions between the cultural heritage and scholarly communities, there are still too few examples of successful partnerships that allow each community to bring their strengths to collaborative digital projects. And lastly, in order to address the lack of specialized tools, it is important to understand the barriers to special purpose TEI tool development and adoption.

I have identified four broad reasons that may begin to address the lacunae between the aspirational goals of the TEI Guidelines and the TEI community, and the realities that may be a factor in preventing interoperability, reuse, and the wider development of TEI-specific tools:

1. The philosophic principles underlying the creation of thematic research collections;

2. A divergence of tag usage (not tag abuse) in (if I may mix my metaphors) the kosher flavors allowed by the TEI. This is due to great flexibility that TEI affords, which, in turn, has led to its adoption by many research communities across many disciplines. It is, however, also an impediment to a sharing of data, even within a defined discipline or research community;

3. A lack of tools and services that take advantage of TEI encoding to enhance sophisticated searching, datamining, and visualizations;

4. A variance in semantic content; inconsistencies for example, in named entities (people, geographic, organizational) between projects or authorities, as well as multiple authorities describing the same domain.

I will discuss these four points in turn.

The first, although not necessarily the most insurmountable impediment to interoperability, is the philosophic approach behind the development of scholarly digital archives or thematic research collections. The term for this genre, conceived in the 1990s, may have first been used in Ireland in October 1999 in a talk by Daniel Pitti at a seminar series organized by the Computer Science English Initiative at University College Dublin [7]. His talk, Thematic Research Collections: A New Genre in Humanities Publishing introduced a concept that has gained currency in the intervening years. Several years later Carol Palmer described this new mode of scholarly communication in her 2004 chapter in the Companion to Digital Humanities as »a new genre of scholarly production [...] digital aggregations of primary sources and related materials that support research on a theme«. [3]

Another description from the Tibetan & Himalayan Digital Library is insightful. Here inclusivity is paramount, but only within the project’s own borders:

A thematic research collection begins with the selection of a scholarly theme, which could be an author, a genre, a movement, a city, a historical period, or a canonical body of literature […] It is thus intentional in that one formulates a criteria and then builds a collection based on that criteria […] The collection then accumulates the relevant resources in primary, secondary and reference literature, and then actively integrates them in a single, interlinked medium, unlike a traditional print collection.

Another characteristic is that […] a thematic research collection also functions as a publisher […] it facilitates and organizes focused research on a particular theme or area, such that it integrates the activities and interests of archivists, librarians, publishers, and scholars […becoming] projects that constitute collaborative reference works without traditional limitations on length […]. [8]

The editors and designers of Tibetan & Himalayan Digital Library have taken on the multiple roles of scholar, librarian, and publisher, building a self-contained information universe. Outside resources are brought in and regularized to work within the norms and boundaries of the collection. New resources are conceived to work within the preexisting structure. Tellingly, nowhere in this description is the notion of how the collection might interact with sources outside its own demesne. According to this philosophic approach, the thematic research collection accumulates rather than collaborates.

This brings me to my second point. Although in 2003 John Unsworth predicted that »the genre of scholarship that will replace the book will be the thematic research collection« [4], yet one might today ask: is the thematic research collection itself under threat? There are persistent problems of funding, the bar to entry is still extremely high, and issues of sustainability are even more pressing than a decade ago. While in the 1990s it was reasonable to assume that users would come to each of our collections and learn its idiosyncratic navigation and design, as well as its unique regularization and search paradigms, we are no longer under those illusions. The majority of users want to perform searches as transparent and simple as those carried out within the ubiquitous Google search box. Many are willing to forego the sophisticated search paradigms based on TEI encoding in favor of a quick information fix (if we even provide them with that option). In fact, they may be willing to forego our collections altogether.

On the other hand, there has been the growing realization that over the last fifteen or so years a large number of TEI-encoded texts have been created by the library and the scholarly communities to varying encoding depths to further different research goals. While the TEI is the underpinning for the majority of these collections, its use is so varied (and at times idiosyncratic) that it is extremely difficult to create a homogonous resource without substantial data massaging and human intervention.

A case in point is the experience of NINES (Networked Infrastructure for Nineteenth-century Electronic Scholarship). Initially the NINES team thought it would develop a repository (in an architecture like Fedora) within which all the content resources it collected would be housed. It assumed that »great emphasis should be placed on content and metadata standardization with the further assumption that all NINES resources would be uniformly coded, hierarchically organized, and archived from a centrally served location.« After some months of investigation and testing, they drew the conclusion that »[s]ubsequent research and development have persuaded us that this top-down, centralized approach is not the best way to proceed.« [5]

In this top down approach, each content item was to be encoded according to a NINES-flavored TEI schema. It, along with a METS wrapper, was to be delivered from a single content management system. As new content items came into the repository, contributors would be asked to »position them explicitly within an interpretive hierarchy or stemma based on the concept of the ›work‹ which would be expressed in METS«. [6] Within a year the NINES development team decided that the structured markup approach would not sustain the community into the future. What the white paper does not describe in detail was the data with which they were working. Some of the projects, such as Romantic Circles, were still in HTML. Moreover, the HTML for Romantic Circles had been created over many years by many authors and could not easily be mapped onto a new standard. Other projects which were drawn on to test their approach had used the TEI as a point of departure for developing their own DTDs, such as The Rosetti Archive and The Blake Archive. Other projects, such as the Poetess Archive or The Walt Whitman Archive used fully-conformant TEI. As a result of the difficulties of migration, the NINES project team decided on a different approach. As their white paper relates:

Although our initial, centralized and standardized model for NINES would promote future tool-building and data migration, we are now persuaded that NINES must be understood as a social system, especially as it gains traction in a scholarly community still constrained by traditional paper-based communication conventions.

While the development team saw the value of texts encoded or at least described by a TEI header as the or at least an ideal solution, it was felt that maintaining such a system by humanities scholars after the initial development period was completed would be extremely challenging. Although in the first instance trained metadata specialists would describe each object, it was felt moving forward that traditional humanities scholars could not be relied on to create the consistent, rigorous metadata that the system necessitates to function smoothly. As they wrote:

We cannot set the bar for participation in NINES too high: perfect compliance with standards for markup, metadata, interface, and archiving will slow the growth of the resource at its most critical juncture. [7]

NINES thus adopted a social network approach as opposed to an aggregated top-down hierarchical one. Currently NINES’ primary vehicle is a targeted bibliography for nineteenth century scholarship (via Collex, a tool developed by the project). It is an impressive set of links to distributed online resources in which resources are interoperable via the bibliographic fields as defined by the Collex schema. Collex does not necessarily get the reader to a digital version of the resource, rather, it provides the reader with the knowledge of the resource.

While the index created by Collex is an excellent resource, it is a far cry from their initial conception. The rationale as described in the NINES white paper to move away from this structured repository approach to a social network of hyperlinks is instructive. As related in the white paper, it was felt that on the one hand, traditional humanities scholars could not be expected to climb the long learning curve of the TEI, and on the other that the level of effort to create a homogeneous set of TEI-encoded documents for interchange was unsustainable given the project resources. Interchange has taken on a new meaning for the NINES community. It is the bibliographic references which are made compatible, not the objects themselves.

Why would the developers of NINES be satisfied with a socially tagged bibliography rather than access to the full text of the documents themselves? One reason might be that most scholars still don’t care how they get their primary or secondary sources: they just want to find the text, print it out, and read it. And while many thematic research collections utilize rich encoding, frequently access to that encoding is limited or poorly understood by a general readership.

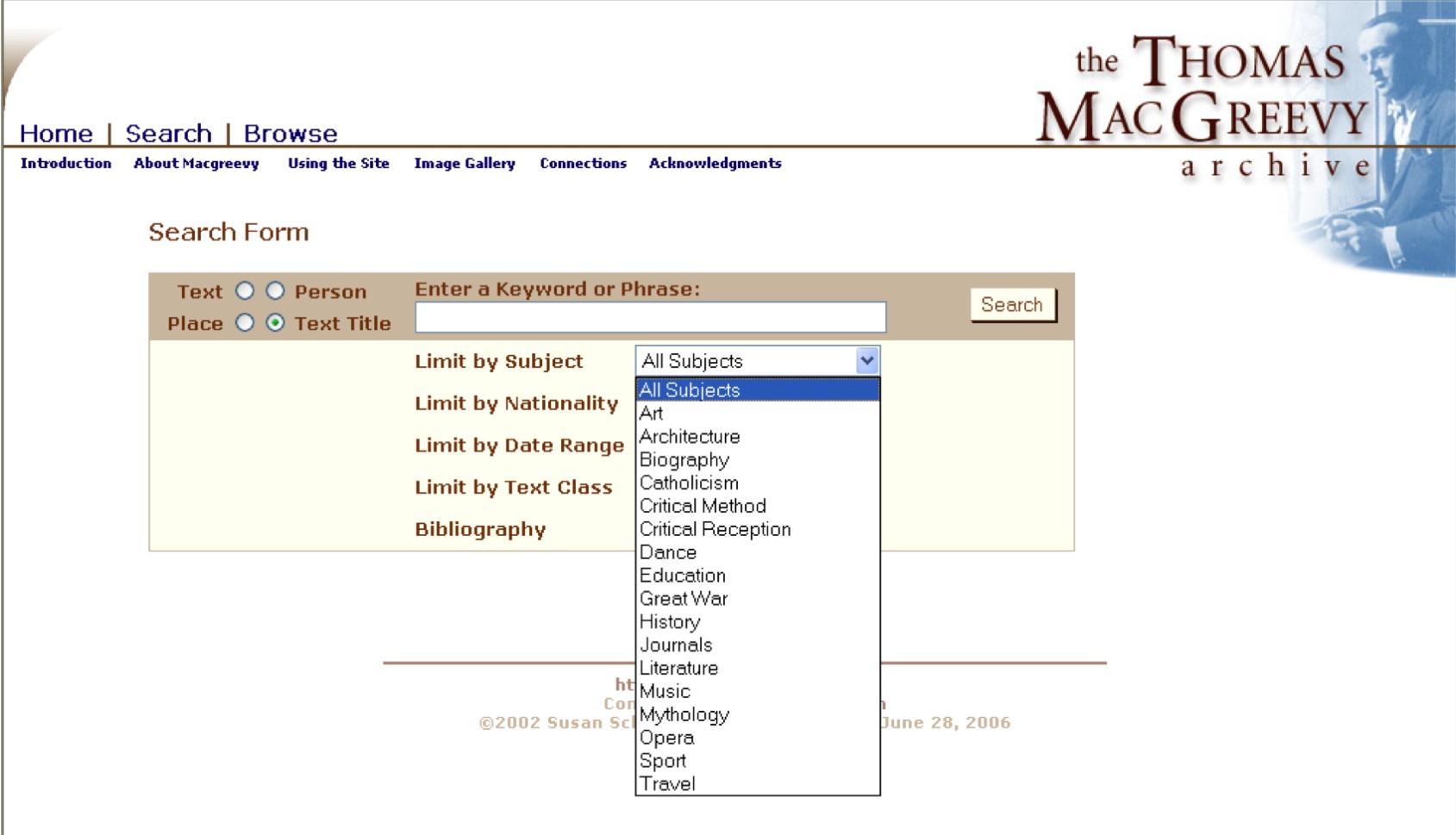

This was brought home to the editors and designers of The Thomas MacGreevy Archive. We conducted usability test on the Archive’s previous site design and found that users tended not realise that searching by nationality was the nationality represented by the text’s content rather than the nationality of the author (although, by and large, all the articles on the site are written by MacGreevy). See Figure 1.

Screen shot from the previous version of Thomas MacGreevy Archive’s advanced search page.

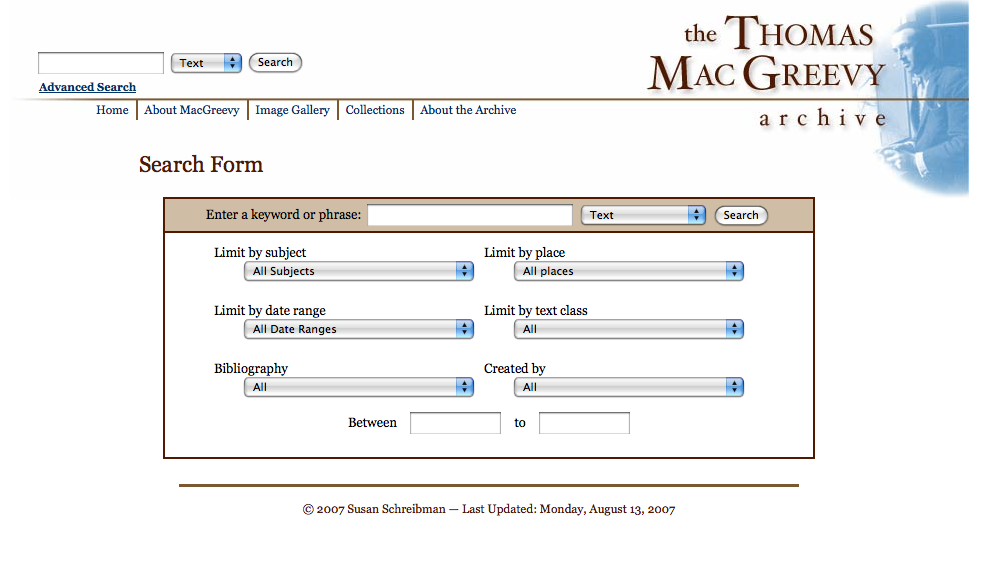

The current advanced search page (see Figure 2) attempts to address some of the semantic difficulties in translating TEI tags to concepts more easily understood by users not familiar with the tagset.

Figure 2: The current MacGreevy Archive advanced search page.

As mentioned previously, most humanities researchers still use digital resources as if they were print. Once they have their sources neatly printed out and sorted in piles, they conduct the real research themselves. And the ways in which we have constructed our thematic research collections lend themselves to that treatment. We still present text in codex-like ways to be read within a narrative context. What we have created is an easily-accessible way to find and print out texts. The scholarship of constructing the archive is so un-transparent and devalued that most of our peers see nothing wrong with citing the original source rather than the online resource in their bibliographies.

This brings me to the third reason that the TEI may not be utilized more frequently as an interchange format: we have not yet leveraged the advantage of machine readable text. We have not developed a suite of tools and services that take advantage electronic texts to facilitate sophisticated searching, datamining, and visualizations. We have not demonstrated to the research community the advantages of electronic text beyond the ability to find them on the web and print them out.

Most publicly available visualization tools, such as TextArc, or the suite on IBM’s Many Eyes, or some of the tools available via Tapor utilize ASCII text and are limited to performing analytics on one document. For many of these tools, a dense text like James Joyce’s Ulysses has to be broken into chapters to be used at all. This is, of course, the ongoing work of MONK (Metadata Offer New Knowledge [10]), a joint project of the University of Illinois at Urbana Champaign and University of Chicago that is investigating datamining and visualization across hundreds or thousands of texts. But not unlike the experience of the NINES developers, it found that interoperability on TEI-encoded texts developed by different projects was virtually impossible without creating a common tagging baseline and ignoring much of the more sophisticated scholarly project-specific encoding.

Another key area that may account for the lack of interchange is semantic barriers, both in tag usage and divergent practices in named entities. An example of how the former inhibits adoption of tools created for TEI texts is the Versioning Machine (VM) [4]. The VM is a framework and an interface for displaying multiple versions of text encoded according to the Parallel Segmentation method [11] of the TEI Guidelines. While it provides for features typically found in critical editions, such as annotation and introductory material, it also takes advantage of the opportunities afforded by electronic publication to allow for the comparison diplomatic versions of witnesses, as well as the ability to easily compare an image of the manuscript with a diplomatic version.

The choice of developing the tool to work only with this method of parallel segmentation of recording variants (the Guidelines offer two additional methods) was taken as much for expediency in development as for philosophic reasons (it was the method which most closely mirrored the developers’ philosophic approach to texts and textuality). [8] Over the first few yeas of the VMs existence, it was downloaded consistently but fairly infrequently (about 30 downloads a year). Over the past two years, however, this has increased substantially to as many as a dozen downloads a week. This is due to a number of reasons, including greater awareness of the tool, special sessions at workshops and summer schools at which the tool is demonstrated, and more scholarly editors choosing to work in TEI.

As the downloads have increased, however, so have the requests for new features. The Versioning Machine has been developed without grant funding and with a very small (albeit changing) development team who often honed their technical skills on the back of its development. While the feature requests are not unreasonable and well within TEI practice, when taken as a whole, they form a set of requests that have the effect of cancelling each other out or creating an XSLT that is bloated with many templates to deal with a particular nuanced encoding. While it is possible for the VM developers to tell those making the requests to add templates to their downloaded version of the VM so that it conforms to their encoding practice, it is not practical. The people making the requests are scholarly editors with little time and prospect of learning XSLT well enough to create or adapt templates in what is already a fairly complex XSLT.

While the VM was designed as a general purpose tool to serve a fairly narrow community of users, divergent encoding practices make it difficult to serve its intended audience without a development team able to meet new requests. If this were a commercial product, continued development would be part of its ongoing work. But for many small tool development projects without proper funding, ongoing support becomes difficult to balance with other obligations. Thus many of these tools have very short lifespans as the effort to migrate them to new versions of the TEI, keep up with new technologies, or simply to respond to a growing user community becomes untenable. Perhaps what is needed is a tools vault hosted by the TEI Consortium where editorship of these tools may be assumed by others in the community (perhaps part of the remit of the Special Interest Groups) if it was felt that the tool was valuable enough to be sustained. If our system of scholarly rewards valued this activity as much as peer-reviewed publication, it might be easier to convince younger scholars to spend their scholarly capital in this way.

However, even if we could agree on a specific tagging practice for a particular document type or within a certain disciplinary period or genre, there looms the issue of semantic inconsistency in named entities. This brings me to my last and final reason: we have not achieved semantic interoperability on the scale many thought would be possible during the first decade of the TEI’s existence. Many projects don’t follow a standard named entity scheme. There are many reasons for this. When the MacGreevy Archive was begun in 1997 there was no web access to authority files. The one copy of Library of Congress Authorities at University College Dublin (were the project was begun) was in the cataloging department of the library and we could consult it only upon appointment. At that time we were regularizing as many as 50 new names a day, making it impractical to consult the hard copy, so we decided to create our own authority list for internal use. The list included substantial apparatus, birth and death dates as well as a brief biographical note on each person.

Moreover, even if the project had had easy access to the Library of Congress’s Name Authority File (to which the British Library contributes) many of the Irish names being regularized (i.e. those who are not writers or subjects of writers) would not have been included, and there was no comparable Irish source to consult. Ten years later, the situation has not greatly improved for Irish studies scholars. This is, however, set to change. Over the past decade substantial work has gone into creating an Irish Biographical Dictionary: 9,000 entries will be published in print form by Cambridge University Press in 2009, but there are 51,000 additional names in the project’s database which could form the basis of an online resource.

Even for projects starting today in disciplines that are much better resourced there may not be clear paths forward. In the field of Art History for example, one must choose between the Getty Thesaurus of Art and Architecture and the Library of Congress Name Authority File. This is not only true for personal names, but for subject headings. While the divergences in practice between titles of published works have a higher threshold for consistency, there are still difficulties in identifying the same work across multiple languages or identifying works that do not have titles given to them by their creator (such as the vast majority of works of art, folk and primitive art and tales, and many genres of music). Even if we could agree on a minimum standard encoding practice to which all documents would conform (possibly the ongoing work on TEI Tight would meet this need), these issues of semantic interoperability would also have to be reconciled.

What would it take for the TEI to be an interchange format once again? Is it possible to overcome the inconstancies in semantic practice; the natural tendency that most humanities scholars have in not sharing their research; and the real barriers to interchange as fostered by the philosophic approach to thematic research collections? Of all the issues discussed in this article, convincing projects to share texts may (surprisingly, given the nature of the system of rewards for humanities scholars) be the easiest to overcome. The experience of the MONK is a case in point. While MONK was extremely successful in convincing partners to share their base texts as to create services across project boundaries, the difficulties in uniformly retrieving semantic content – both via tags and content items – has proved challenging.

The issues discussed above are of central concern to the Digital Humanities Observatory. Unlike some the research communities where there has been a great number of early adopters, Irish studies has few. The number of large-scale TEI-based thematic research collections can be counted on less than one hand. But rather than look at this negatively, the DHO is viewing this as an opportunity to learn from the lessons of the past and create individual thematic research collections that provide for a base level of semantic operability. The DHO is adopting three methods to achieve this. The first is to serve as a knowledge resource for the rest of the HSIS network. This is being achieved through consultations on projects, assessing their needs and goals, and recommending strategies, technologies, and standards. The second method is in the area of education, through lectures, standards workshops, symposia, and summer schools.

The last method for promoting digital humanities in Ireland is in the creation of a shared repository to store, preserve, and provide access to the complex range of e-resources created in the humanities in Ireland. To do this, the DHO is recommending national standards to help ensure a level of interoperability to enable the fullest exploitation of existing national research collections and data repositories. The TEI will be one of those standards. How we help scholars achieve their intellectual goals using TEI as a semantic wrapper while achieving a level of harmonization with other standards and media types will be the challenge the DHO faces.

At this juncture in this new field, it is possible to say with more certainty than we could ten or even five years ago, that the face in which we present our intellectual work, the interfaces that our users interact with, is the most ephemeral. The DHO and its partners have the opportunity of being a laboratory for the digital humanities community in learning the lessons from the past, as well as the more recent work of projects like NINES and MONK, to develop an interoperable framework cognizant of not only past and present practice, but flexible enough to accommodate future developments in technology and intellectual practice that we cannot even begin to imagine.

The enormous successes of the TEI in developing an interoperable framework for information interchange, and the ongoing difficulties posed by a multiplicity of philosophic approaches to encoding practice and lack of semantic interoperability, are lessons for the DHO as we embark on the development of a community of practice, in creating a multimodal technical framework, and in developing methods to provide for a level of intellectual and semantic interoperability flexible enough to take advantage of future developments but rigid enough to provide a level of semantic interchange of which even Google would be envious.