The Thomas Moore Hypermedia Archive commenced in September 2005 as a three-year group project funded by the Irish Research Council for the Humanities and Social Sciences, with the aim of creating a pilot version of the archive, to be made freely available on the web. Thomas Moore was an Irish writer who was born in Dublin in 1779, and was active in the first half of the nineteenth century. From relatively humble beginnings, he moved to London and set out to forge a literary career with some measure of success. He commanded a good deal of celebrity in his lifetime and was a close associate of Lord Byron, with whom he shared a friendly rivalry and by whom Moore was only slightly bested in terms of sales and popularity. The reputation that he enjoyed at the height of his fame began to diminish in the years after his death in 1853, and faltered in the twentieth century until the last thirty years, which have seen a gradual re-awakening of interest in Moore’s role in the formation of Irish cultural identity. One of the central motivations behind the creation of the Thomas Moore Hypermedia Archive is to provide access to reliable scholarly texts of Moore’s writings so that this type of research, a long-overdue reassessment of a major figure in Irish literature, might continue.

To this end, a long-term objective of the project is to collect the complete poetic, musical and prose works of Thomas Moore (a decidedly onerous task for a writer with a steadily productive output over a forty seven-year career), but the immediate concern of the pilot period of the project is to establish a framework for the continued growth of the archive. The pilot version will contain sample editions of Moore’s poetic, prose and musical works, which will serve as models for how further instances of each of these compositional forms might be incorporated into the archive in future. [1] The archive is very much a work-in-progress, and with each of the three participants coming to the project with backgrounds in literary studies, but no practical experience in creating electronic editions, the learning curve has been sharp and the challenges have at times seemed mystifying, but not without moments of satisfaction and encouragement. What I hope to outline in this paper are some of the experiences I have had while working on my section of the archive and how using the standards of the TEI has helped to bring shape and clarity to some of my ideas about the edition.

The section of the archive that has been the focus of my research involves the creation of an edition of Moore’s book-length Romantic Orientalist poem, Lalla Rookh. The current obscurity of this work is contrasted with its contemporary nineteenth-century popularity, as Longman published nine editions within a year of its initial publication, having already taken the unprecedented step of paying Moore an advance of £3,000 before having seen one word of the poem. The publication history of the poem is a long and detailed one which encompasses legitimate and pirated editions in English, translations in several languages and other incarnations of the text. A theatrical pageant based on the text, with accompanying music by Gaspare Spontini, was performed on stage in Berlin at the Royal Court of Prussia in 1821 and many other cities staged operatic and theatrical adaptations of the poem. It was set to music by Robert Schumann and Anton Rubinstein, and one edition of the poem [2] contained illustrations by John Tenniel, the celebrated Punch cartoonist who would illustrate the first edition of Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland four years later. Several sections of the poem were also separated from the text, and printed along with accompanying musical notation. The hypermedia edition is ideally suited to including audio and visual components (both of which play a major role in a comprehensive understanding of Moore’s career and work), and its extensibility enables the possibility of future additions to the archive, as well as ensuring that further material can be easily incorporated into the edition as it is discovered.

Lalla Rookh has not yet been the subject of a scholarly edition. There is documentary evidence of editorial work being done on the poem before it went into print in May 1817, in the form of a set of Corrected Proofs that are currently held at the Pierpont Morgan Library in New York. This work was probably shared between Moore and a compositor at Longman’s publishers: many of the corrections are indicated by strokes, dashes and simple proof correction marks, and are thus difficult to identify as Moore’s with any certainty. Unfortunately, there is no record of how Moore treated the proof copy of Lalla Rookh because he began writing his Journal (which was published in a six-volume edition, edited by Wilfred S. Dowden between 1983 and 1991) in August 1818, sixteen months after he would have received the proofs for the first edition. There is, however, a letter written to his mother on 13 May 1817 (about a week before the first edition was published) in which he mentions his labours on the poem: »Strange to say, the work is not finished yet, but I hope to give the last of it into the printer’s hands before Saturday«. [3] He had little active interest in the textual integrity of the poem once it had been published; a letter from July 1817 proclaims that Moore is eager to correct some of the poem’s »many many errors« before the third edition is printed, [4] but the account books of Longman publishers make no mention of costs related to corrections. [5] A Journal entry from more than ten years later, when the fourteenth edition of the poem was about to go to press, reveals a more diligent author: »employed myself, as yesterday, in correcting some sheets of Lalla Rookh, for the new Edition that is preparing – the first time I have read it since it was published«. [6] The absence of Moore’s influence on the print editions of the poem has directed the focus of much of my work towards the development of the text of Lalla Rookh through the stages of its composition to the publication of the first edition; while the focus of this is clearly on the role Moore had in shaping the poem, there is an equally feasible project in following the extra-authorial growth of the work through its various stages of publication, piracy and adaptation, and this will hopefully form part of the edition at a later date. For the moment, as the examples in this paper will show, the documents that will comprise the hypermedia edition are the three extant manuscript drafts, corrected proof copy [7] and first edition of the poem.

The emergence of electronic editions of literary works has presented the scholarly editor with a whole new range of possibilities and challenges. Freed from the restrictions and requirements imposed by publication in book format, the editor is in a position to take advantage of those features of the medium that enable the full representation of sources and documents that in a print edition might be processed by the editor and then relegated to a footnote or endnote. Though the editor need no longer make decisions like this, equally important and significant editorial obligations lie elsewhere.

While working on encoding the three manuscripts, proof, and first print edition of Lalla Rookh, one of the results I have been trying to achieve is to encode the five texts in such a way that the user of the archive will be able to trace the development of any single line of the poem, and see the extent to which it has changed (or remained the same) through the stages of Moore’s composition and revision to its first appearance in print.

The approach that I have taken thus far has been to consider each of these stages in the composition of the poem as a separate and independent entity. In a more traditional print edition that takes the first edition as copy-text, the first four of these stages might be considered superfluous: each a necessary but negligible step in the process of bringing the literary work to an ideal state of ›completion‹, and, ultimately, to print. This is their status at one end of the scale of their utility; at the other, the editor of a variorum edition will treat each stage as being significant, identifying and recording all of the changes and variations in the text with each successive witness. This is very similar to my approach to the edition of Lalla Rookh, but the main difference lies in the visualisation of these changes and variations. The editor of the print edition must devise a system that the reader can use to establish what parts of the text have undergone changes between the first manuscript draft and the first edition. Generally, this system will take the form of a base text that is chosen by the editor according to whatever principles they exercise, and a textual apparatus to indicate where variants occur. This method, while emphasising the importance of variant readings and pre-publication textual witnesses, is usually bound to define and demonstrate these variants in relation to a chosen base text, simply because of the nature of the codex format and its layout. When the editor makes a decision to choose a particular base text, as they inevitably must, they are conferring a degree of implicit superiority upon that text because it is the one complete text that readers are faced with each time they open the variorum volume. By the same token, the variant readings, simply through their relegation to an apparatus at the foot of the page appear to have an inherent inferiority and superfluousness in their relation to the ›main‹ text.

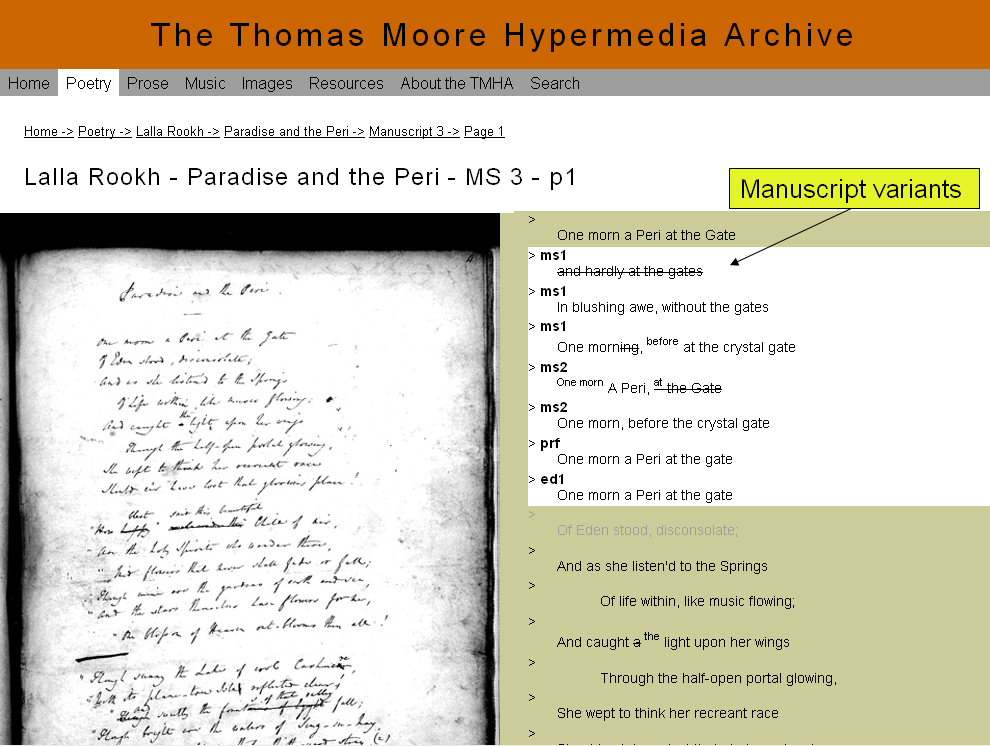

The aim of the electronic edition of Lalla Rookh is to eliminate the hierarchical organisation of textual witnesses that is implicitly created by the chronological succession of drafts, [8] and that is also a necessary consequence of the materiality of the printed book. The edition establishes equality between the five texts of the poem by allowing the user to choose any one of them as the basis of their enquiry. From this particular point, the user will be able to compare any line of verse with other versions of that line (if they exist) in the four other texts of the poem. For example, if the user decides to examine Moore’s third manuscript draft of the poem, they will navigate through facsimile images of the manuscript on a page-by-page basis, each of which is accompanied by a transcription. If a particular line attracts the user’s attention, say, line 40 of Paradise and the Peri, they may click on a marker beside that line to activate a drop-down list which will reproduce in toto the versions of that line from the first and second manuscript drafts, corrected proof copy and first print edition.

Figure . Screenshot from Lalla Rookh hypermedia edition with drop-down list of variants.

In this fashion, the user may compare full transcriptions of versions of that particular line in up to five witnesses, rather than having to visualise these changes for themselves by means of an apparatus of variants. Clicking on the line marker a second time will de-activate the drop-down list.

This feature of the edition is achieved by a number of steps. Firstly, each line of each textual witness is assigned a unique identifier, for example <l xml:id="l40ms3"> is the opening tag for the fortieth line of the third manuscript of the poem. Where there is more than one version of a line within a single textual witness, what appears to be the final version of the line is tagged according to the method above, and earlier versions of the line are tagged with the same identifying line number, but with decimals appended to mark their early status. So, the penultimate version of line forty in the third manuscript would have an opening tag <l xml:id="l40.1ms3">, a version prior to that <l xml:id="l40.2ms3">, and so on. Due to the fact that Moore did not keep any record of the dates on which he made changes to his manuscripts, deducing the sequence in which three versions of a particular line in a manuscript were composed involves a certain amount of speculation. In many instances, I have managed to decide on this sequence with a fair degree of certainty, owing to the physical placement of the lines in the manuscript, changes in ink, and other factors; it is worth acknowledging at this point, that whatever advantages are offered by encoding for the presentation and investigation of literary texts, these are the kinds of subjective and evaluative decisions that it is difficult to imagine a computer making with any more assurance than a human editor.

Once all of the lines from the five texts have been given unique identifiers, the next step is to make cross-witness correspondence explicit. In this process, the textual editor must first complete the work of finding links between the verse lines of the different texts, deciding what level of similarity there must be between two lines before they can be said to correspond. Once again, this is traditional scholarly textual work and depends to a large degree on the subjective interpretations of the editor. Given the same textual problem, two editors may decide on two very different approaches. When the linear association is established, it is then a matter of encoding this correspondence, and I have chosen to do this using the @xml:id that has been assigned to each line, and a combination of <link> and @targets, as described in version P5 of the TEI Guidelines. [9] The encoded texts of the five witnesses are combined within the same XML file along with a <linkGrp type="correspondence"> which contains a list of entries of this form: <link targets="#l42ms1 #l42.1ms1 #l52ms2 #l40ms3 #l40pro #l40ed1"/>

In effect, what this piece of code identifies is that there exists a correspondence between one line from the second and third manuscript drafts, corrected proof copy and first edition, and two lines from the first manuscript draft of Lalla Rookh. This group of links provides the means by which the drop-down list of variants can be created in the edition (this is achieved by an XSLT processor which retrieves the verse lines that correspond to each of the attributes listed in @targets), enabling a clearer visualisation of Moore’s compositional methods from any given point in the five textual witnesses.

One of the challenges of preparing an edition for the electronic medium is how to sensibly organise the potentially large mass of textual and documentary witnesses; or, as Kenneth Price asks, »What separates wisdom and madness in a project that sets out to represent everything?« [10] While this work might appear like an unevaluated accumulation of texts and documents, the fact of the electronic edition’s seemingly limitless potential for including documentary material prompts the question of how best to steer editorial practice towards wisdom rather than madness; on a smaller scale this question is posed when the texts of the edition’s documents come to be processed. The problem that then confronts the editor is how much detail to encode? A light encoding might involve a choice to identify only the major structural elements in the text (lines, line groups, sections of the poem, and perhaps its metrical forms), whereas a more detailed mark-up might recognise instances of intertextuality and references to other works, or avail of the opportunity to provide critical and contextual commentary on certain parts of the text. But the editor need not stop there. He may decide to mark-up mentions of persons and places, and then categorise them as real or fictional; to list the occurrence of specific poetic conventions and devices, or to note the physical features of the document, marking every change of hand, every use of pen and pencil in the manuscripts, and so on. The number of features awaiting the tags of the scrupulous editor is colossal and, as the evolution of the TEI Guidelines acknowledges, continues to grow.

The section above describes what steps are taken to structurally encode Lalla Rookh in a manner that is most conducive to demonstrating the genetic development of the text of the poem from its earliest manuscripts through to publication. The very availability of such evidence of Moore’s compositional practices dictated to a large degree the direction that the edition would take; but the ability of TEI to accommodate more than one interpretative approach to a text or set of texts (›orientation‹ to the text, as Peter Shillingsburg has called it) [11] means that other potentially useful ways of interpreting and examining the poem have been acknowledged through the encoding. For instance, with the parallel display of scanned manuscript images and transcriptions in the Lalla Rookh edition, an important task has involved encoding the frequent changes and corrections that Moore made in the manuscripts. While the display of corresponding lines in different textual witnesses has been enabled by using <link> and @targets to collect @xml:id values attached to <l> elements, instances of Moore making changes within those individual lines have been identified with <subst>,<del> and <add> tags.

Another feature of Lalla Rookh whose significance can be elaborated in the electronic edition is the curiously studied nature of its composition. As the writer of a poem which prided itself on its realistic depictions of the landscape and life of the Orient, it is worth noting that Moore never travelled in the region, but assumed his knowledge through examining many accounts of travels to the Middle East and dissertations on the customs of its peoples by noted scholars such as Sir William Jones (1746–94) and John Richardson (1740/41–95). In a journal entry, Moore himself notes:

All the customs, the scenery, every flower from which I have drawn an illustration were enquired into by me with the utmost accuracy, and I left no book that I could find on the subject unransacked. [12]

He briefly mentions a number of his sources in footnotes to the poem, but the electronic edition can effectively expand upon these by providing a much fuller bibliographical record for the sources and, where possible, link to the portion of the text that may have influenced Moore’s composition. While a print edition might achieve something similar, the electronic edition can provide more immediate access to Moore’s primary sources, either by providing extracts that clarify the context, or by directly linking to the web-based texts of the source, or facsimiles thereof.

For example, this couplet from Lalla Rookh:

›I know too where the Genii hid

›The jewell’d cup of their King Jamshid,

has a footnote appended, which reads »›The cup of Jamshid, discovered, they say, when digging for the foundations of Persepolis.‹ – Richardson.« [13] The very bookish nature of Moore’s research for the poem makes the manner in which he uses his resources all the more interesting. Exhaustive citation was not a concern of the poet, though, so the electronic edition can usefully display the greater contexts of Moore’s references. It might be achieved in this case, by providing the full entry in John Richardson’s A Dictionary, Persian, Arabic and English, from which Moore extracted the reference:

(Jem (or Jemshid) The name of an ancient king of Persia, whom they confound with Bacchus, Solomon, and Alexander the Great. He is the subject of much fable; almost the whole circle of the arts and sciences being supposed to have been invented by him, or Pythagoras, whom they make his prime minister. The cup of Jemshid, called jami jem (discovered they say filled with the Elixir of Immortality when digging for the foundations of Persepolis) is more famous in the East than even the cup of Nestor among the Greeks; furnishing the poets with numberless allegories and allusions to wine, the philosopher’s stone, divination, enchantments, &c. &c.). [14]

By encoding the verse and notes in this fashion, the greater context of Moore’s research is made available to the user:

<l>"I know too where the Genii hid</l>

<l>"The jewell’d cup of their King Jamshid, <anchor xml:id="note1"/></l>

…

<note xml:id="tm-note1" place="foot" resp="TM" target="#note1">"›The cup of Jamshid, discovered, they say, when digging for the foundations of Persepolis.‹ – Richardson." </note>

…

<note resp="JT" target="#tm-note1">(Jem (or Jemshid) The name of an ancient king of Persia [ . . . ] </note>

In effect, what this approach introduces is a system of multiple annotations which are associated to one another. Not only can the user access the many annotations that Moore provided for the text of his poem, but they may also refer to further contextual annotations that are composed by the editor.

These are just a few examples of how encoding Lalla Rookh for the Thomas Moore Hypermedia Archive has been approached. There are many other examples, each of which represents a different ›orientation‹ to the text; as more of these ›orientations‹ are observed, the mark-up becomes more detailed and complex and the possibility of invalidating the structural hierarchies becomes greater. This is not to say that this is impossible to achieve, but simply to acknowledge that the decision to identify a specific additional feature of a text can potentially require a lengthy revision of the structure of the existing mark-up to accommodate it. And this is where imagining the needs and requirements of the user will help to decide upon the degree to which the text is tagged, and which of its features it is desirable to identify.

Having begun work on this project with an interest in Bibliographical and Textual Studies, but blissfully ignorant about the practicalities of encoding a literary text, I have found that a daily acquaintance with the standards and procedures outlined in the TEI Guidelines has helped me to develop my understanding of the nature of texts and their means of display. When the editor of the print edition encounters some textual variety in the stages of the genesis of the poem, the scholarly print medium demands that they make a choice about whether and how this variety should be represented – whether in a reading text, a variorum, or some kind of eclectic text. So, the editor negotiates with the limitations that the print volume imposes upon him or her, to prepare an edition that will present in as clear a manner as possible those aspects of the literary work that its reader is most likely to want to see. Ultimately, however, each act of the editor must proceed from a distinct ›orientation‹ to the text; while in a print edition, no single editorial act can conform to more than one of these ›orientations‹ at a time, the structure of the electronic edition is more suited to presenting texts that completely fulfil the requirements of each of these orientations, whether they be bibliographical, documentary, authorial, sociological, or aesthetic. [15] By encoding a text from a number of the perspectives allowed by the TEI Guidelines, those of us working on the Moore Archive anticipate that we might be more equipped to satisfy the varying interests of a range of Moore enthusiasts than if we were preparing a print edition. While the textual variants in my own edition of Lalla Rookh do present a similar challenge in choosing the most appropriate manner of representation, the linear linking method described above eliminates the necessity of prioritising any one text of the poem, effectively achieving the edition’s purpose of demonstrating the importance of equality among textual witnesses when considering the manner of a literary work’s composition. Thus far, this edition of Lalla Rookh has been shaped by the fruitful convergence of established standards in scholarly editing and in text-encoding.